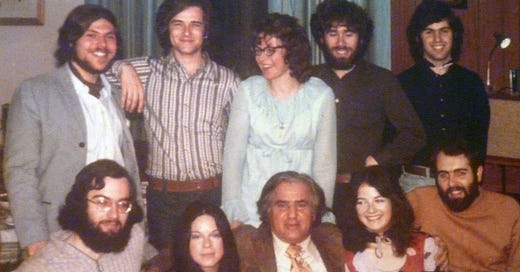

It’s hard to believe the slightly fuzzy photo above was taken 54 years ago. This was at a party attended by some of the members of Irving Layton’s York U. poetry workshop in 1971. Left to right, bottom row first: Brian Flack, Sylvia Weinstock, Layton, Carolyn Grasser and (I think) Colin Rutledge. Top row: Robert Ulmer, Ken Sherman, Bernice Lever, me, and David Hertzman.

It was a good time to study Canadian and creative writing at York. Other faculty members at York’s main campus then included Eli Mandel, Miriam Waddington (I was her TA one year), Frank Davey, and the Tunisian-Canadian writer Hédi Bouraoui. Michael Ondaatje taught at the Glendon College campus.

If you don’t recognize the name Irving Layton, you should look up some of his poetry. A half-century ago, he was still writing and publishing prolifically, viewing himself as a blend of visionary Jewish prophet and street-fighting lover of women, and was widely regarded as one of Canada’s best poets (especially by himself). Many writers you might know today took his poetry workshops/classes. In the group photo, those who went on to publish the most were myself, Brian Flack (several novels and a poetry collection), Bernice Lever (several poetry collections, plus editing Waves magazine), and Ken Sherman (ten poetry collections, three prose works) , whose latest book I will review below.

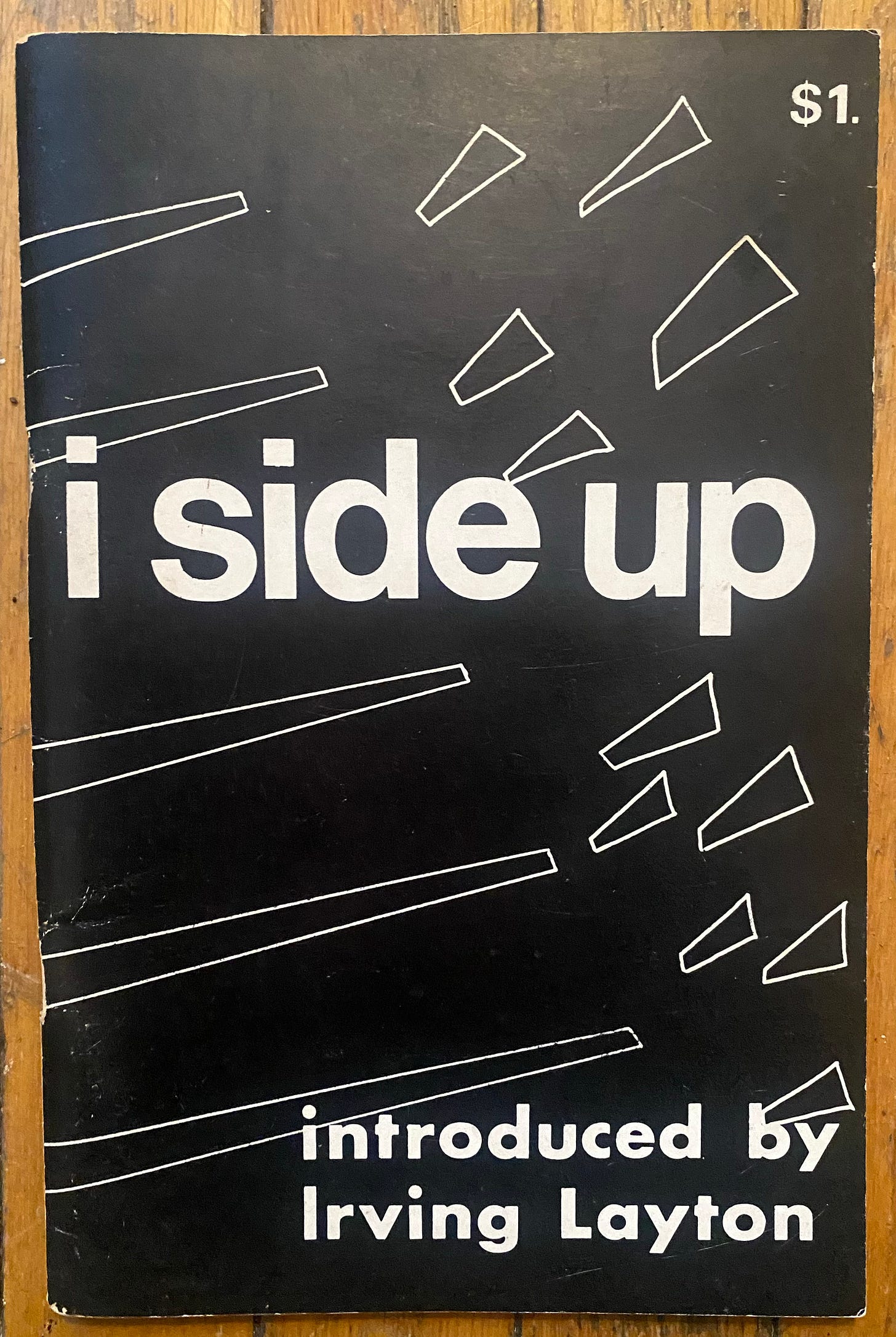

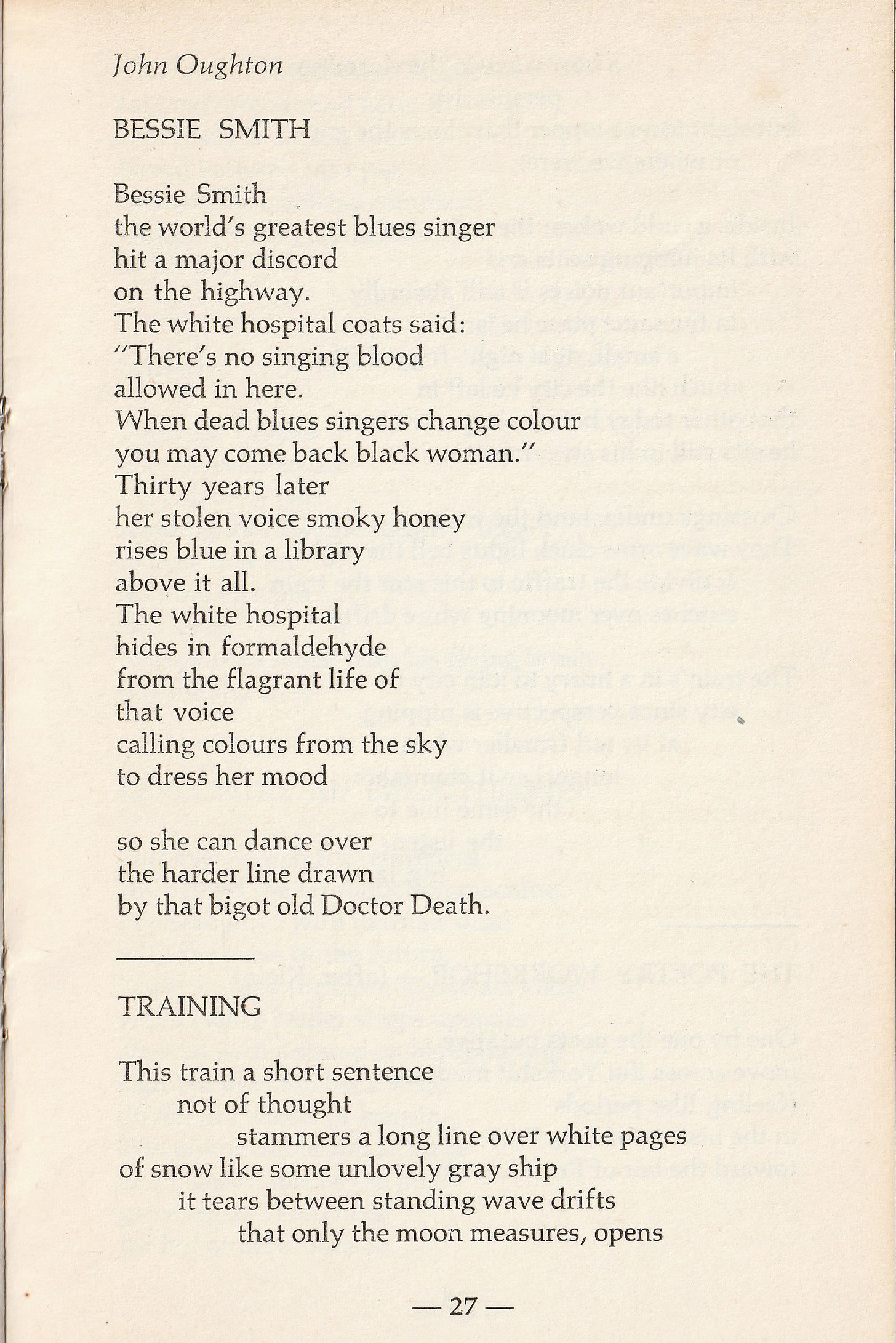

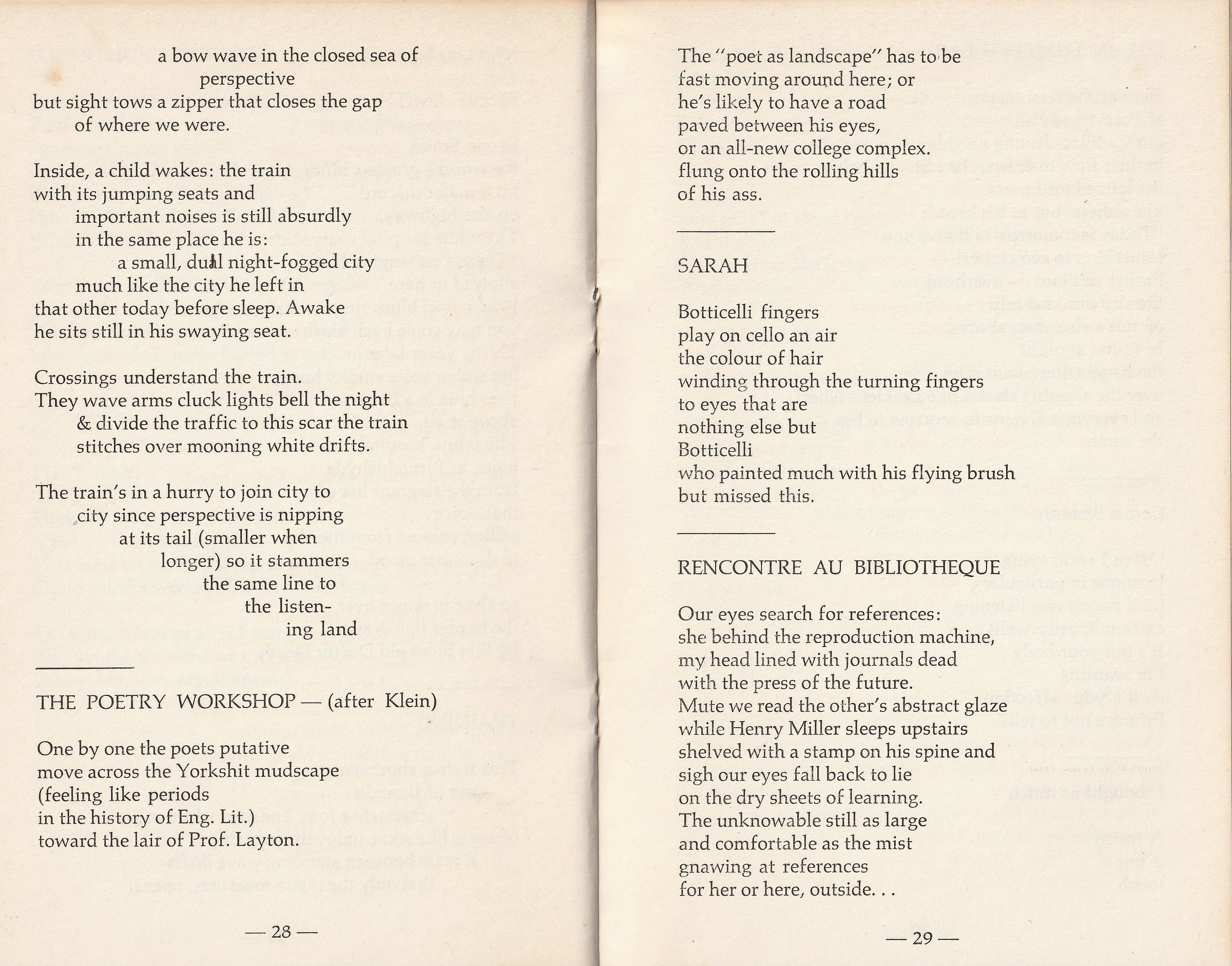

Layton chose what he considered the best work by we fledgling poets and assembled a group chapbook titled i side up. He included a few poems by the then-little-known Pat Lane, who was not in the workshop, but had received Layton’s newly-invented York Workshop Award for a promising new poet. In typically restrained prose, Layton wrote in the introduction: “Students at York and other universities, tired of the nerveless juiceless junk offered them by semi-literates or earnest pedagogues could do worse than study [Pat Lane’s poems] as possible models or points of departure.”

Below are photos of the cover, and my own pages.

Along with his old high-school friend friend, Robert Ulmer, and the beautiful Sylvia Weinstock, Ken and I became friends. We both enjoyed playing guitar (although he was better than I was). A few years later, when I was having trouble finding stable employment, Ken suggested I try his day job: teaching writing courses at Sheridan College. “You just do your classes, then you go home and write poetry,” he advised me. I’m glad I took his counsel.

By the end of our workshop, I was sure Ken was the most talented poet in our class. Now, he’s among the best of our poets in English. He’s not a self-promoter, so when you see a list of the ten or so supposedly greatest Canadian bards, he’s rarely mentioned on them. But he should be.

Ken Sherman, more recently .

OK, finally, the review.

Meditation on a Tooth, by Ken Sherman. Guernica Editions Essential Poets series. 96 p.

Well, if Sherman’s so good, where’s the proof? I cite the title poem. You might think a single tooth wouldn’t be enough to inspire a long poem in nine parts. But you’d be wrong. Ken’s ability to connect the everyday to the cosmic and eternal reminds me of Blake’s lines, “To see a World in a Grain of Sand/ And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,/ Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour,” although Sherman’s sensibility is darker, less mystical and more ironic.

Now, about that tooth: Its diagnosis as a failed chomper after decades of active service took Sherman by surprise. Considering what this means, he connects embodied feelings of loss and ageing to many other things:

”..sweet with blood / but bitter / with the awareness of age / and my departure /from this loving star.” Each section of the poem gives a new twist to the tooth’s significance, as it becomes a family story (“It was pulled by my cousin / Dr. Larry Grossman”), evokes toothless actors and hockey players Sherman recalls from his childhood, along with street person Wild Bill (“my father gave him odd jobs / let him bunk winter nights /with the cats on the cutting table”). Sherman’s father, as readers of his earlier books will remember, was a tailor on College Street who once made custom suits for a local musical group named The Hawks before they became The Band. Check out Ken’s fine memoir “Robbie Robertson’s Tailor,” in Tablet magazine.

The poem continues to make new connections, some literary (Kafka, who kept two of his milk teeth, and Francis Bacon, who described the mouth as “a galaxy of hard stars”). This dental meditation reaches across time and space — “our teeth originate in stars / that eons back swelled /and broke apart violently.” It also touches on the Holocaust, recalling the SS guards who yanked gold teeth from their concentration camp victims. That one poem can extend from that obscene fact to the feeling of wonder in “we should sense / the radiant / continuum” is a tribute to Sherman’s awareness of the complexity of existence and history, the intermingled pain and beauty that is part of being alive on this planet.

Another striking sequence, Work Poems, starts with a tribute to the tree cutting crew who came to a trim a tree on the poet’s property, then recalls the summer and part-time jobs he worked at in his youth,: “The Rides” at Center Island; “Bucky Harris”, a war vet who taught the young Sherman to run the Ferris wheel; ”United Tire Corp”; and “Meat Packing,” which concludes “the smell of this place / clings to the skin.” There are many other poems worth celebrating, and re-reading here, some from his travels to Japan and India, an amusing one about his dogs being hypnotized by his playing guitar, and other pleasures. I’ll leave those for you to discover. This is a fine collection, and not a huge one. Surely you can fit one more Canadian poetry book on that shelf?

Like what you read here? You could buy me a coffee.